Oliffe Richmond (Class of 1936) – Sculptor of the World

Posted on August 13, 2025

Oliffe Richmond (1936), talented student of Friends’, sculptor to the world.

Compiled by Kathy Rundle

Robert Oliffe Gage Richmond (1919-1977), known as Oliffe, spent his early childhood at Gagebrook House, Old Beach, Hobart. He was the younger of two surviving children of Robert Lawrence Richmond, a farmer originally from England, and his Tasmanian-born wife Catherine Augusta, née Gage. Catherine enjoyed some early art education and practiced as a china painter. In 1929, the Richmond family moved to live at 58 Montague Street, New Town.

Oliffe and his sister Patricia attended The Friends’ School from Term 3, 1929. The Headmaster at the time was Ernest Unwin, an educator, scientist, and keenly interested in the arts. He would invite members of the local art community to school to speak to students and took “plein air” painting classes himself “on Tuesday afternoons”. At Friends’, Oliffe enjoyed most studies but was drawn to the arts, winning a school drawing prize as well as participating in sports. He was a member of the 1936 first rowing crew, the 1936 firsts football team and the Interschool Athletics hurdles. Oliffe took on roles such as Form Captain and was popular with his classmates. A female friend recalled “with his dark hair, olive skin and brown eyes,” he was “much sought after”.

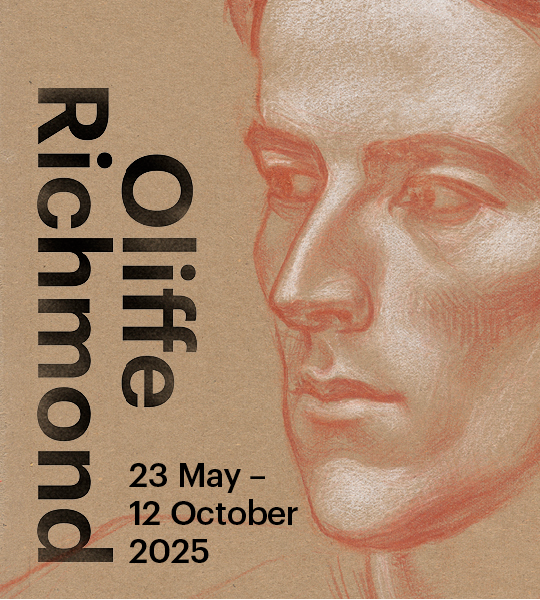

After graduating from Friends’, Oliffe enrolled in 1937 at the Hobart Technical College, in both Fine and Applied Art courses. He was greatly influenced by his Art School teachers, among them Jack Carington Smith, Lucien Dechaineux, and Mildred Lovett. Throughout this period, he explored every available fine and applied art subject, developing a particular fondness for life drawing. He pursued out of school opportunities such as mask making with the local Repertory Theatre and in his home studio he modelled in clay and even cast some plaster models. He also took ballet lessons with Beattie Jordan to increase his understanding of bodies to improve his figure drawing.

During this time, Oliffe began an intense relationship with fellow art student and acclaimed artist Eileen Brooker. He also had the chance to work with Amos Vimpany, Hobart’s most prominent stonemason, from whom he gained valuable, lifelong knowledge of materials, tools, and carving techniques. Another important influence on his development as a sculptor was New Zealand artist Alison Duff (later Laird).

While studying in Hobart, Oliffe also earned his small aircraft licence, and with the outbreak of the Second World War, he volunteered for the RAAF. However, he was rejected due to an astigmatism. He overcame disappointment and mobilized in the Militia in 1940. His first three years as a soldier were spent in Hobart and Brighton and was able to continue art school studies part time and exhibit with The Art Society of Tasmania (a group he had helped establish).

Oliffe found military service largely dull, monotonous, and unfulfilling, with barrack life in Victoria proving particularly disheartening. However, his time training in Melbourne offered a welcome reprieve—allowing him to attend concerts and art exhibitions, make frequent visits to galleries, and study art books at the library. He briefly joined a Borovansky Ballet class, took modelling classes at RMIT, and attended life drawing sessions led by sculptor Ola Cohn. Continuing his art practice became a vital escape from the oppressive routine of camp life, and whenever possible, he also took part in art classes run by the US Army at the American Red Cross Centre in Melbourne

By mid 1944 he was transferred to the Jungle Warfare School at Canungra in southern Queensland where his frustration with “this stupid existence of constant training exercises” peaked. Accepting a transfer to Lae in New Guinea, provided relief and allowed him to experience real jungle beauty. The New Guinea environment excited his sensibilities and inspired his continued passion for making art capturing New Guinea’s exotic flora and fauna, as well as different human forms. He drew scenes of army life, with a ‘sculptor’s perception’. Even in his fully resolved chalk or pencil portrait studies of soldiers, he was concerned with the head as a solid form rather than a face as “a window to a soul.”

His final transfer in 1947 to Sydney was followed by a bout of malaria. Oliffe then plucked up the courage to enrol at the East Sydney Technical College to study sculpture. Viewing a Henry Moore exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales that year “bowled Richmond over” reporting “he [Moore]is the only one, the only one”.

During that busy year Oliffe won a New South Wales Government travelling scholarship. In June he sailed for England first to tour Europe and then to take up an opportunity as assistant to Henry Moore. He worked as Moore’s assistant until 1951 when he succeeded him as a teacher in sculpture at the Chelsea School of Art. From 1954 Oliffe’s sculptures were included in major group exhibitions in London and other British cities, in Paris, Oslo, Zurich, Switzerland, Sydney, Melbourne, and the USA. Solo exhibitions followed, in Belfast (1964), New York (1964), London (1965), Canberra, Melbourne (1967), and Sydney (1968).

A sense of the monumental had long been a characteristic of his work. It found dramatic expression in his final 1970’s series, massive assemblages in wood. He had meditated for long periods among the megaliths of Stonehenge and was sustained by the sense of being part of a great and ancient tradition. He died in 1977 at his home in Kensington, London.

In 1989, both TMAG and QVAG held a retrospective exhibition of Oliffe Richmond’s work. Today, these institutions house a substantial collection of his works on paper, selected sculptures, and sketchbooks.

From 23 May to 12 October 2025, TMAG is holding a solo exhibition of works on paper together with sketch books and a few sculptures from their Richmond collection, which is freely available to everyone to visit.